Rann Run: How we set the record for the fastest crossing of the Rann of Kutch in the Volkswagen Virtus GT

We take the entire range of Volkswagen’s India 2.0 cars to the Rann of Kutch and set a national record with the Virtus GT in the process

We’ve been to the Rann of Kutch more times than I can remember, but I had never seen it like this. Strong winds had whipped up a dust storm, making it impossible to leave the safe confines of the car. We tried to get out — pushed the doors open only to be welcomed by a gale that was tearing at our clothes, blowing hats into the wind and wreaking havoc on our gear by getting that fine dust everywhere. Visibility was close to zero. The dust cloud had blotted out the sun. It looked like a scene out of Mad Max, or even Interstellar — Miller’s planet, but make it dust. It felt just as desolate. Barren flat land for hundreds of square kilometres, with no one inhabiting it.

The Rann is a place of extremes — you will find dry, cracked earth for most of the year but come the monsoons, this low lying land floods with sea water and becomes impossible to set foot in. In the summers, temperatures soar as high as 50 degrees, while dropping below freezing point in the winters. Over half an hour and 20km later when the dust storm hadn’t blown over, the photo and video crew looked at each other with dread. They knew we weren’t turning back, and would have to brave the storm. After all, we were there on a mission.

The mission? Crossing the Rann in Volkswagen’s latest — the Virtus and the Taigun. It is anniversary time, after all — two years since the Taigun arrived, a year since the Virtus launched. In that time, both have shifted goalposts in their segments. They deliver on VW’s core — safe, fun, solidly built cars but do so while being attuned to the needs of the Indian customer. They have been made in India, for India.

To be fair, this is Taigun territory. SUV territory. The surface in the Rann is just loose mud, and while it does look perfectly flat, you’ve got deadly ruts all over — left behind by the trucks mining salt in the area. The good ride quality soaks up the imperfections on the surface but more impressive is the body control which was keeping the Taigun stable despite the speeds we were pulling. And of course, there were the engines — the strong 1.0 and 1.5 TSI engines, benchmarks in their respective classes for their innate ability to combine performance and efficiency into one balanced package.

The Taigun? It is hard not to fall in love with it. It captures the essence of VW’s bigger SUVs like the Tiguan, but packages it in a size perfect for India, without compromise on performance or dynamic ability. Before the Taigun came out, SUVs in this segment were floaty, soft, they would roll, understeer. But then the Taigun showed them how it was done. This is an SUV that can actually corner. This is an SUV that can deliver on the Thrill of Driving. We’ve run one in our long term fleet, driven one to the absolute edge of the country where no civilian car has gone before, and every time we get behind the ’wheel of one, we are a little more floored. Out there in the Rann, the Taigun GT was pulling triple-digit speeds effortlessly, soaking up the road surface and everything that came along with it beautifully. But the Taigun isn’t the hero of this story. It is simply here to accompany its fellow stablemate — the Virtus.

What is the Virtus doing in “SUV territory”? Fun fact: the Virtus was intentionally engineered to have SUV-rivalling ground clearance. 179mm, if you’re the numbers kind. You see, like the Taigun, this is a car that is made for India, and designed with proper inputs from the Indian teams. VW realised that a big pain point for sedan owners in India was the ground clearance, and they’ve addressed that with the Virtus. It is made for Indian roads. Good roads, bad roads. Or in today’s case, no roads.

Okay, we’ll admit it — we called the Virtus out at first. Said that the high ground clearance sullies what would otherwise have been a killer stance. But after spending so much time with the Virtus, it’s hard not to ignore the upside of that distance between the underbody and the ground. It could keep up with the Taigun, and was actually more comfortable because the lower centre of gravity allows for softer suspension without compromising body control. So here you are — a sedan that is a driver’s delight. One that retains the bits that we love about sedans, without any of the compromises.

Crossing the Rann was surreal. The deeper we got into the Rann, the harsher it got. The Rann doesn’t have any reference points even on a clear day, navigating it with just a couple of feet of visibility was incredibly hard. At some point, one of the cars got separated from the pack and what ensued was 10 minutes of calling out to each other on the radio, completely blind until we could reunite and carry on. All the while, the heat was bearing down on us — a steady 43 degrees Celsius after the sun was up in the sky. Crosswinds lashed at us. Lunch was served somewhere along the way — a support 4x4 pick-up truck doubled up as a buffet counter and the wind ensured we had a generous amount of sand as seasoning. These were some of the harshest conditions we’d ever faced at evo India. But the cars? They were unperturbed. Okay, dust did get everywhere but that aside, they soldiered on, kept us cool in the cabin, and covered the 73km through the Rann from Zinzuwada to Palasava without trouble.

On the other side, we caught wind of something. A record. For the fastest crossing of the Rann. Right up evo India’s ally. The record set in 2019 stood at 34 minutes 10 seconds for the total distance of 73km. Some back of the napkin math led us to conclude that this meant averaging 127kmph over the whole distance. Hmm. Possible, but it was tough. Visibility was already low so navigating was hard, those suspension killing ruts could spring up out of the blue and the crosswinds made a high speed run risky. Over to Sirish in the Virtus GT.

If it were easy it wouldn’t be much of a record. But did it have to be so bloody difficult? Aatish has already laid out for you, in eloquent detail, the severity of the conditions we are dealing with but I’ve been coming to the Rann since before he even graduated to full pants, and I’ve never, ever, seen such vicious gale-force sandstorms. The digital cluster on the Virtus is showing 44 degrees, but the sun is nowhere to be found. For three straight days we have all been waking up at 3 in the morning to get to the Rann in time for what truly is the most spectacular sunrise you will see in India, and three days we have been eating sand for breakfast. Sand for lunch. Sand for tea. And then cleaning the cars in anticipation of but no sunset joys. Rohit, our photo chief, has brought along a 500mm lens to frame the cars against the setting orb in the sky but all it is doing is eating sand. As are we. The wind wants to rip off my hat and take it across the border into our not-so-friendly neighbour’s territory. I have to lean into the wind to take a few, laboured steps. Nobody can hear anybody. And this is the third straight day of this nonsense.

We should have known better. From tomorrow, the first of June, the Rann is officially closed, timed with the annual arrival of the monsoons. The heavy, pregnant, threatening clouds are already here. We’ve even been treated to spits of rain, enough to make even our guides nervous. A plan is in place for the fastest exit out of the Rann in case the drops turn into a stream. Aatish has already run through what happens in the monsoons, and none of us are carrying our swimming trunks.

All of which means today is D-day. There’s no ‘let’s wait for the weather to lift tomorrow’. It’s now or come back in September once the waters have receded and the Rann has dried up. And we will have to repeat our exercise of the last two days once again because these aren’t permanent roads. These are dirt tracks that are created by the first tractors and salt trucks that go in after the rains and they tend to follow whatever is the driest path. The track leading from one end of the Rann to the other keeps changing, adding or reducing a kilometre, sometimes two kilometres. This year it is 73.4km, up by 400metres, and the past two days have been spent doing reconnaissance runs making proper pace notes.

I mention things are bloody difficult, didn’t I? It’s not just the sand storms but the daunting, threatening record we have to beat. The record stands at 34 minutes and 10 seconds for the 73km run, with a max speed of 170kmph and an average of 127kmph. It was set a year before lockdown, in an SUV, and by colleagues from a magazine we hold in very high esteem. Those guys know how to drive, but I didn’t expect them to know how to fly down dirt tracks that only rally drivers can tackle so expertly.

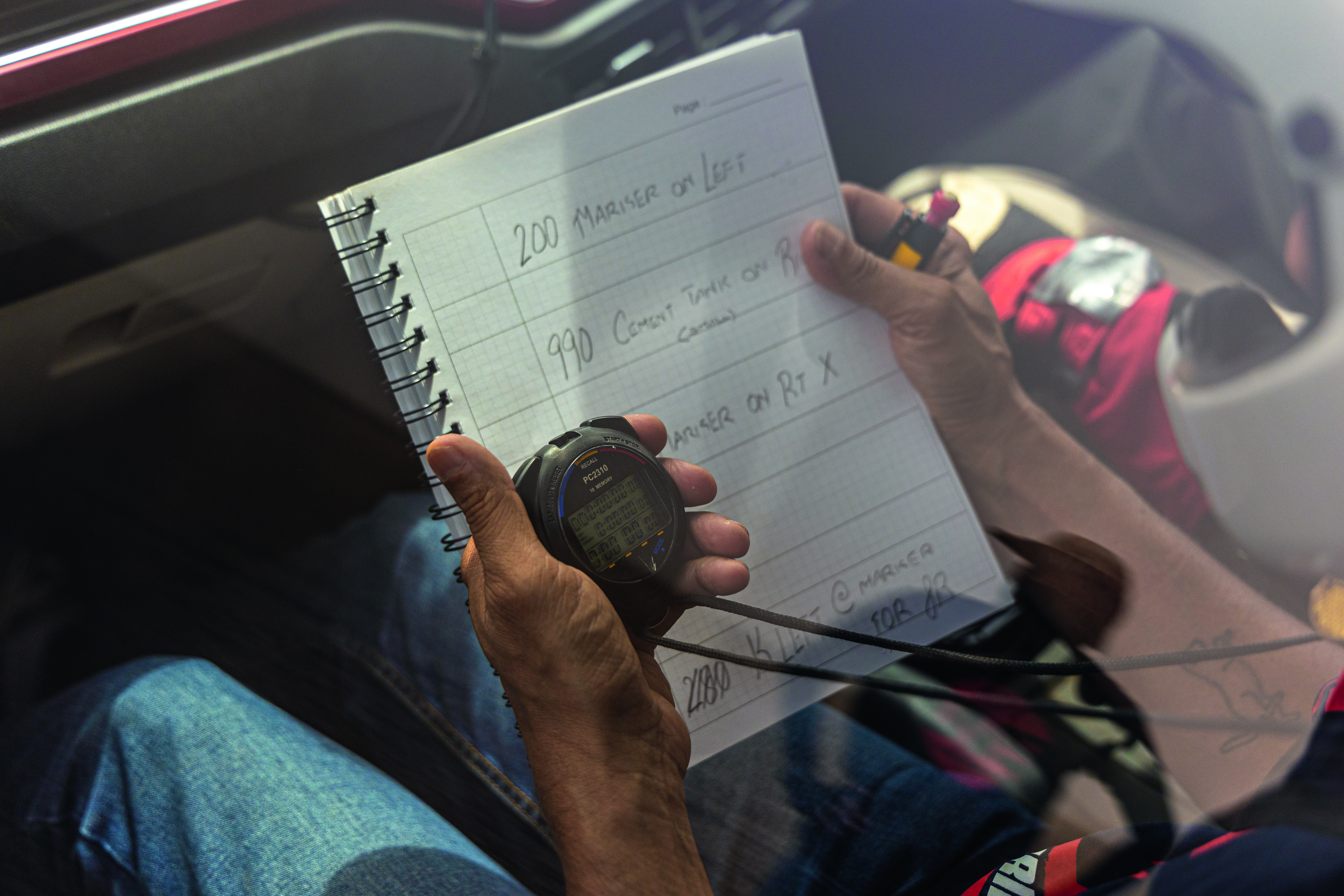

And so we have called in the reinforcements, specifically my co-driver from my national championship rallying days – Nikhil Pai. Together we bagged 40 trophies, including the very first victory for the VW Polo in the INRC, and after I hit pause on rallying to focus on this magazine, he went on to bag another 40 trophies together with the ultimate prize – the Indian national championship.

This is an out-and-out rally effort. There isn’t a single patch of tarmac, it is all dirt tracks – some super-fast sections with very fast corners that will throw the car sideways at well into triple-digit speeds; some tight and loose sections that are severely dug up and will need us coming right down to second gear; and very many dips, ruts, bumps and triple caution sections that will fling us into our not-so-friendly-neighbour’s arms if we don’t have proper pace notes.

That’s what we have made. And with visibility being so bad, I am hoping and praying that I’ve made accurate notes.

And this is why we picked the Virtus. 15 years, I’ve only rallied a car – more than half of it in a Volkswagen. I know how a car behaves at, and over the limit. And I’ve always believed that for performance enthusiasts a car is the way to go. I’ve also always said that for The Thrill of Driving the VW Group India 2.0 cars are the way to go and this is my pick, the Virtus GT.

It looks good and as motorsport engineers will tell you, if a car looks good it invariably is fast. But that’s besides the point. More importantly the torsional rigidity of the MQB-A0-IN platform is 30 per cent more than the Polo I rallied with so much success. It delivers great body control. It makes the Virtus predictable at and over the limit. I know, I can feel what it is doing and apply just the right corrective measures. And the suspension has enough compliance to go flat-out over the bumps. In our road tests we have said that the ride comfort improves appreciably with speed. We are now going to put our money where our mouths are. And we have an audience to witness it.

Last year at the launch of the Virtus I’d grumbled to Ashish Gupta, head of VW Passenger Cars India, about why a sedan needed to sit as high off the ground as an SUV, much to the detriment of its stance. Now I’m eating my words. Had the Virtus not had 179mm of ground clearance there’s no way I’d be able to attempt this record. Ashish is here with his team, Abbey Thomas head of marketing, Gagan Mangal head of marketing communications and press and Krittika Nangalia from the PR department. They are here to witness evo India set another India Book of Record with their India 2.0 cars, following up on the Border Patrol last year. No pressure then!

Ashish and his team along with one of the adjudicators from the India Book of Records heads to the finish line. The second adjudicator heads with us to the start line. The crew from the Rann Riders have helped us sanitise the entire section but we only have three hours. Time for two runs at the max.

I’ve dusted off my Sparco helmet, in hibernation ever since lockdown. It has a Peltor intercom wired in so I can hear Nikhil’s notes without any distraction. And once the helmet comes on, once I slip on the gloves, that’s when I become another animal. With all outside noises blocked off that rally helmet focuses the mind and gets rid of fears, especially of a car sliding under you at 150kmph.

Roll up to the start line. DSG gear lever in Sport. Left foot on the brake. I know brake torquing doesn’t work so I wait for the count down. 3-2-1, off the brakes, flat on the gas and we are off. The stock Apollo tyres scrabble for grip, dirt flying off its grooves as we launch the Virtus GT. I’ve switched off ESP, the spinning wheels will dust off the loose top layer and find some traction. The first half of the run, from Palasava to Zinzuwada is the super-fast section. Long straights which would have been easy but now needs a quarter turn of lock to counter the cross winds. Nikhil’s calls are something like 500 8-right, a long pause, then 600 7-left, which means a 20 degree right hander after 500 metres followed by a 30 degree left hander after another 600 metres. With the Virtus accelerating hard and getting up to some serious speeds I have to brake for even the easy corners and the long straights in between, with no visual markers, makes it difficult to time the braking points. The loose surface means the Virtus hangs its tail out on the right hander, then is sideways in the left hander, every corner needing a bit of corrective lock, but it is all predictable. There are no surprises. You know exactly how the Virtus is going to behave. In fact the only surprise is we barely feel the sections marked ‘caution bump’. Hitting those bumps at 140-150kmph completely flattens it out and I now muster the courage to go flat-out for the single cautions, letting the suspension compliance do its job. The double and triple cautions though, that’s another matter, and we have to hit the brakes hard to slow the car down, tapping the downshift paddle on the DSG to get some engine braking into the mix.

12 minutes in and we are at the half way point, well within the target time, but here’s where it become tricky. It now gets rougher, there are tighter corners, and with no visual markers navigation is also very tricky. Nikhil’s calls are now coming harder, faster. There’s more emphasis on the cautions to make sure I stay sharp and focussed. And just to let our brain work better we’ve left the air-con running. It’s over 40 degrees outside. Might as well stay cool and collected inside the car, thus avoiding any costly mistakes. And even though we are flat-out the air-con is keeping us nice and chilled.

25 minutes in. The home stretch. This is where we were expecting the suspension to go soft, the heat allied to the tremendous load we are putting on the stock dampers finally making the oil boil over and lose its viscosity. Except the Virtus continues to handle predictably. There’s no bottoming out. No lurid tail-out moments. I can continue to trust the front end, throw it hard into the corners and rely on some of my old rally-reflexes to catch the slide and keep the throttle pinned. The fact that I am using the DSG gearbox also makes things easier for me. Tap for down, tap for up, snappy gearshifts and my free left foot stays focussed on left-foot braking. Once you get over the launch phase, this DSG box is quicker than the manual.

31 minutes. The final stretch. The roughest part. I miss a call and go wide, luckily there’s only loose mud that slows us down and I wrestle the Virtus back on track. Somewhere in the back of both our minds is the 5-star G-NCAP crash test ratings. Neither of us wants to put it to the test but it also adds to our confidence in the car, helps us push that extra 5 per cent. And that’s what makes all the difference. Breaking records like this is touch and go. I remember the last rally that I did, the only rally that I did without Nikhil in the co-driver seat, with three stages to go I was closing in on Karna who Nikhil was co-driving for, and then I made a mistake, went off, lost confidence and never closed that gap. Had to settle for third.

The same can happen here. Nikhil, in his measured tones, tells me to calm down. Breathe. He is monitoring the time and distance using the Monit GPS unit, he knows we did a damn good first section and have some time in reserve. I recognise the last couple of corners, I know we are almost there, the adjudicator is at the flying finish, Nikhil reminds me there’s a tight corner just after the finish so not to go flat out else we will crash immediately after the finish, and we are through.

Nikhil hits the stop watch. “Time?” I yell. “32 minutes 57.7 seconds,” says Nikhil, helmet still on, tone still calm and measured. I back up to the finish line to cross check with the adjudicators. “32 minutes 57.7 seconds,” says Ritesh Chanpura, the adjudicator. “A minute faster!” adds Ashish Gupta. This might be the worst conditions we’ve ever encountered in these parts but the Virtus GT punched through it to clock the fastest crossing of the Rann of Kutch, proudly flying the flag for driving enthusiasts; The Thrill of Driving flag.